By Enrique Jiménez | ![]() Cite this page

Cite this page

Jiménez, E., “Cities and Libraries,” Cuneiform Commentaries Project (2015), at http://ccp.yale.edu/introduction/cities-and-libraries (accessed November 13, 2024)

This page provides a short overview of the most important Mesopotamian libraries that held commentary tablets. The first part of the page describes libraries found in Assyria; the second part, Babylonian libraries. The socio-cultural context of the commentary tablets is briefly discussed at the end of this page.1

Mesopotamian libraries can be divided into three categories: (1) temple libraries, such as the library of the Bīt Rēš in Uruk or the library of the temple of Nabû in Kalḫu; (2) palace libraries, such as the libraries of Ashurbanipal in Nineveh; and (3) libraries belonging to private individuals, such as the libraries of the Šangû-Ninurta family in Uruk. These categories, however, are not as clear-cut as they may seem: colophons on dozens of tablets found in temple or palace libraries indicate that the tablets in question belonged (or had once belonged) to private individuals.

Assyrian libraries and tablet collections

Kalḫu

The city of Kalḫu (later Nimrud) was the main residence of the Assyrian kings from 864 to 706 BCE. The only important repository of cuneiform tablets that has been found in situ is the library of the temple of Nabû, which has yielded around 280 tablets dating from ca. 800 BCE to the end of the Assyrian empire. The library included many divination texts, rituals and incantations, and literary and historical works. None of them are marked as property of the temple of Nabû. Colophons on a number of tablets refer instead to private owners, among them members of Nabû-zuqup-kēnu’s family (see below). Only four commentaries have been found in this spot: for a list of them, click here.

The most important tablet collection stemming from Kalḫu was found not in Kalḫu, but in Nineveh. Around one hundred tablets once owned by the scribe Nabû-zuqup-kēnu, a descendant of an illustrious scribal family, have been recognized among the ca. 30,000 tablets of Ashurbanipal’s libraries found at Nineveh. No less than 21% of these one hundred tablets are commentaries, one of the highest ratios from any library or tablet collection.

Aššur

The city of Assur (modern Qalʿat Šerqat) was for many centuries the political and religious center of Assyria: even after the capital was moved to Kalḫu in 864 BCE it kept its religious primacy among the Assyrian cities, until its final destruction in 614 BCE. Around 11,000 tablets were excavated in Assur, of which only 20 are commentaries. The largest discrete library discovered in Assur belonged to a private house, that of the Baba-šumu-ibni family, which yielded 1,242 tablets. Many of them bear colophons mentioning Kiṣir-Aššur, his father Nabû-bēssunu, or his nephew Kiṣir-Nabû, all of them “exorcists,” as their owners or scribes: hence the modern name of their dwelling, “House of the exorcist” (Haus des Beschwörungspriesters). Most of the tablets found in this spot contain rituals and incantations related to the family’s profession, but there are also many literary, historical, lexical, and other types of texts. Nine commentary tablets were discovered in this house, mostly on ritual and incantation texts (for a list of them, click here.) They show distinctive Assyrianizing features, such as the use of the particle mā to introduce and structure explanations, and at least some of them were probably composed in loco.

Few commentaries have been found in other libraries from Assur. One of them is the most important manuscript of the Principal Commentary on Šumma Izbu, VAT 9718 (CCP 3.6.1.A.a), which was found in a small library in a private house. Another private house yielded one of the few available school tablets with a commentary excerpt (VAT 10071 = CCP 3.6.1.A.l).

Ḫuzirīna

The city of Ḫuzirīna (modern Sultantepe) was an Assyrian provincial town situated between Urfa and Ḫarrān, which was briefly excavated in 1951/1952. Some 400 tablets were found there, written between 718 BCE and the end of the Assyrian empire by members of a family of šangû-priests. Only three commentaries have been found in this spot: for a list of them, click here.

Nineveh

The city of Nineveh, near modern Mosul, served from 705 BCE until the end of the Assyrian empire as the main residence of the Assyrian kings. It was there that king Ashurbanipal (668 – 631 BCE) decided to establish a number of libraries whose scope can be called almost “universal.” Some 31,000 tablets and fragments were found during the excavations of the mound of Kuyunjik, where Nineveh’s most important palaces and temples were located. The majority of the tablets came from Rooms 40 and 41 of the Southwest Palace. Ashurbanipal furnished his libraries with tablets from all over Mesopotamia. Many tablets from Babylonia were incorporated into Ashurbanipal’s libraries after the civil war between the Assyrian king and his brother Šamaš-šum-ukīn, perhaps as war reparations. Upon their arrival in Nineveh, some of the tablets were newly copied for the king’s libraries and and marked as property of the king with one of the standard Ashurbanipal colophons.

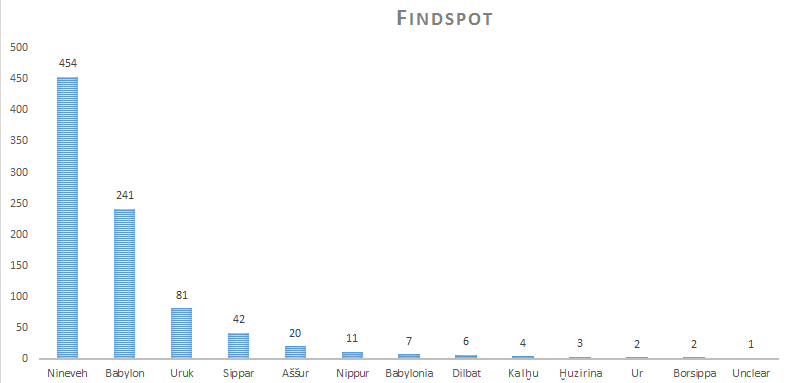

Almost all genres are represented within Ashurbanipal’s libraries, and both in terms of quality and quantity, the Nineveh tablets continue to outshine the manuscripts tradition of other Mesopotamian cities. Commentaries are no exception: around 454 tablets and fragments,2 more than half of all known commentary tablets, were found at Kuyunjik (see a list here). The typology of the Ninevite commentaries reflects the encyclopedic scope of the library: different types of exegetical treatises on all sorts of texts have been found there.

The royal correspondence between the king and Babylonian and Assyrian scholars often displays some of the hermeneutical techniques that can be found in Mesopotamian commentaries: many of them, for instance, provide sophisticated reinterpretations of the protases and apodoses of astrological omens.

Babylonian libraries and tablet collections

Sippar

The main libraries of the city of Sippar were situated in the temple of Šamaš, the city’s most important deity. Around 52 commentary tablets, dating from the Late Assyrian to the early Achaemenid period, were found in different libraries in the god’s temple (see a list here). Most of Sippar’s commentary tablets come from Hormuzd Rassam’s excavations in the 1880s, which unearthed around 35,000 cuneiform tablets, primarily in rooms 53 and 55 of the temple. The commentary tablets from these rooms deal with text of all genres, and include the only known exegetical treatises on texts such as Lugale, the Laws of Hammurapi, and the Great Prayer to Marduk 23.

In 1985/1986, Iraqi archaeologists unearthed a library of nearly 800 clay tablets, found in situ on their shelves, in room 355 of the Šamaš temple. They date to the Chaldaean and early Achaemenid periods. Three commentaries, one on the teratological series Šumma Izbu and two on the hemerological treatise Iqqur īpuš, were found in that room, but they remain unpublished.

Uruk

With ca. eighty tablets, the libraries of Uruk have yielded the third largest number of commentaries, after those from Nineveh and Babylon (click here for a list of them). The Uruk commentaries, especially the later ones, are among the most sophisticated hermeneutic treatises from ancient Mesopotamian.

The earliest commentaries from Uruk were found in the ruins of a library in the Eanna temple, among some 250 tablets and fragments dating to the Neo-Babylonian and early Achaemenid period. Three commentaries on divination texts were discovered in the Eanna (see a list of them here). One of them, CCP 3.4.1.A.h, was, according to its colophon, copied from an original from Borsippa, from where it was brought probably by members of a family of itinerant scholars.

Most of the commentaries from Uruk were found in an area in the eastern part of the city. The area has yielded more than five hundred tablets and fragments, which can be assigned to two discrete libraries. The earlier one, which dates to ca. 400 BCE, was owned by members of the Šangû-Ninurta family and is known as the library of Anu-ikṣur. Like other members of his family, Anu-ikṣur was an exorcist, and his tablet collection reflects his interests: many medical treatises, ritual and incantation texts have been found among his library’s tablets. Around 131 tablets can be assigned with some certainty to his library, of which 33 are commentaries (some 25% of the total). As the rest of the library of Anu-ikṣur, his commentaries are mostly concerned with medical and magical texts. It has been proposed that one of Anu-ikṣur’s commentary tablets (SpTU 1 46 = CCP 4.2.D) is a treaty composed ad hoc for a medical text that is also preserved in the library of Anu-ikṣur.4 This would mean that at least some of the commentaries from Anu-ikṣur’s library were composed in situ by members of the Šangû-Ninurta family. Be that as it may, Anu-ikṣur’s commentaries stand out for their sophisticated explanations and for their keen interest in demonstrating the internal coherence of their base texts.

Another private library, that of Iqīšāya, operated in the same area during the early Hellenistic period, and remained accessible several decades after its owner’s death. Iqīšāya belonged to the Ekurzakir family, a family of exorcists. As in the case of Anu-ikṣur, Iqīšāya’s library reflects his professional interests, although fewer medical treatises and more literary works were found there. Some 153 tablets can be ascribed to Iqīšāya’s library, of which 21 are commentaries, mostly on divinatory texts. A few tablets from the library were written by scribes from Nippur. Iqīšāya’s library has also produced the only tablet from Ashurbanipal’s libraries that has been found in excavations outside of Kuyunjik, SpTU 2 46 (CCP 3.4.4.A.g).

The last important repository of commentary tablets in the city of Uruk is the Rēš temple, the temple to Anu situated to the west of the Eanna complex. It became the leading sanctuary of Uruk after the 5th century BCE. Regular excavations in the temple area discovered a collection of some 160 badly broken tablets, belonging mostly to members of a family of lamentation priests who considered themselves descendants of Sîn-lēqi-unninnī. They comprise many ritual and cultic texts associated with the craft of the lamentation priest. Three of the fragments discovered here may or may not be commentaries (see a list here).

The most important tablets that are suspected to stem from the Rēš temple, however, originate from uncontrolled excavations in the area in the 1910s, and are housed in several collections around the world, most importantly the Louvre Museum and the Yale Babylonian Collection. Some of the colophons of these tablets refer again to members of the Sîn-lēqi-unninnī family: they include CCP 3.6.3.D and CCP 3.1.4.A. Others mention members of the Ekurzakir family, which suggests that they once belonged to Iqīšāya’s library, and were perhaps incorporated into the Rēš temple library at some point: among them are CCP 4.2.M.a (on rituals), CCP 3.4.3.G, and CCP 3.6.3.A, (both on teratological omens). Some of these commentaries may have actually originated in Nippur, or else were copied from Nippur originals.

Nippur

Several commentary tablets found in Uruk may ultimately stem from Nippur, but only eleven commentaries have been found in Nippur itself (click here for a list of them). Only three of them were found in the course of regular excavations: CCP 4.2.A.a, CCP 4.2.B, and CCP 6.1.C. The first two tablets preserve colophons that label them as property of Enlil-kāṣir, lamentation priest of Enlil and descendant of Enlil-šumu-imbi, descendant of Lú-dumu-nun-na, and date probably to the early Achaemenid period (another tablet from the same scholar seems to have been found in the Rēš temple). Two commentaries on the terrestrial omen series Šumma Ālu from Nippur, CCP 3.5.22.A.b and CCP 3.5.59, were written by one Naʾid-Enlil, son of Šamaš-aḫḫē-iddin: an identical copy of the former was found at Uruk, CCP 3.5.22.A.a. The commentaries from Nippur stem from no fewer than five scribal families.

Babylon and Borsippa

Babylon and its sister city Borsippa were probably the most important centers of cuneiform learning in the first millennium. Due to the chances of discovery, the known tablets from Babylon date mostly to the period between ca. 600 BCE and the beginning of the Common Era. Unfortunately most of the commentary tablets found in Babylon come from uncontrolled or poorly documented excavations, so little can be said about their original setting.

Although no tablet clearly datable to the Late Assyrian period from Babylon has yet been identified, colophons of Nineveh tablets often record that they were copied from originals from Babylon or Borsippa: this is the case, for instance, of several of Nabû-zuqup-kēnu’s tablets. The oldest datable commentaries stemming from Babylon were found in the course of the excavations of the Emašdari temple of Ištar in Babylon, and may date to the 6th century BCE. Only two commentary tablets were found here (CCP 3.5.u6 and CCP 3.9.u1).

Most commentaries from Babylon, altogether some 225 tablets now housed in the British Museum, were found elsewhere in the city (see a list here). It has been proposed that many of them may ultimately stem from a library associated with the Esagil temple; others probably come from private libraries.

Many of these tablets preserve colophons that identify the scribes and original owners of the tablets. Some of them, which arrived in London on November 3rd, 1881, probably stem from the Ēṭiru family, one of whose members, a certain Iprāʾya or Šemāʾya, active in the early Achaemenid period, appears in the colophon of two commentaries (CCP 3.1.16 and CCP 2.2.1.B). For a list of the 81-11-3 tablets, click here.

Many of the tablets from the British Museum’s Babylon Collection date to the Hellenistic or Parthian period. They include three commentaries written by members of the Mušēzib family (see a list here), which may date to the 2nd century BCE.

The latest datable cuneiform commentaries, however, a total of nine, were copied by members of the Egibatila family (for a list, see here). Some of them mention parchment scrolls (called magallatu in Akkadian) in their colophons. The latest cuneiform commentary with a date, DT 35 (CCP 3.8.2.B), was written in 103 BCE by Nabû-balāssu-iqbi, one of the scribes of this family. Remarkably, another commentary copied by this scribe, DT 84 (CCP 3.4.1.A.i), is a copy of an extispicy commentary of which many manuscripts are known from Ashurbanipal’s libraries.

Other Babylonian cities

Dilbat, a small city some 30 km south of Babylon, may have been the origin of three commentary tablets (CCP 3.4.3.F, CCP 7.2.u63, and CCP 7.2.u64), but the situation is far from certain.

The important scribal center of Ur has yielded only two commentaries, perhaps from the Achaemenid period (see a list here).

Sitz-im-Leben of the Mesopotamian commentaries

Very few commentary tablets derive from a clearly definable school context. Many, however, have colophons according to which they were copied by “young exorcists” or “junior-apprentices.” A handful include glosses such as “I do not know it” (ul īdi) or “I have not read it” (ul alsi), which also suggests that they were written by young apprentices. Moreover, several colophons state that commentaries were owned by the father of the copyist, which is believed to be an indication that they were copied as an advanced school exercise: this is the case of the late commentaries copied by Nabû-šumu-līšir and Marduk-zēru-ibni, sons of Marduk-zēru-ibni, of the Egibatila family (see a list here).

It is important to note that a vast majority of the commentary tablets were copied from other commentaries, and not copied by dictation or composed in an impromptu fashion. This is indicated, on the one hand, by colophons claiming that the text is a copy of an older tablet, and by paratextual glosses within the text indicating where their vorlage was damaged here and there. On the other hand, some commentaries survive in almost identical copies from several different periods and cities, such as the extispicy commentary CCP 3.4.1.A, preserved in copies from Late Assyrian Nineveh, Achaemenid Uruk, and Parthian Babylon.

Guide to Further Reading

For an extensive overview of the socio-cultural milieu of the Mesopotamian commentaries see Frahm, 2011, Babylonian and Assyrian Text Commentaries. Origins of Interpretation. Ugarit-Verlag, 2011.: 262-316. Pedersén, 1998, Archives and Libraries in the Ancient Near East 1500-300 B.C. Almqvist & Wiksell: CDL Press, 1998. and Clancier, 2009, Les bibliothèques en Babylonie dans le deuxième moitié du 1er millénaire av. J.-C. Ugarit-Verlag, 2009. offer detailed presentations of the libraries and archives in Mespotamia, furnished with extensive bibliographies. George, 1991b, “Babylonian Texts from the folios of Sidney Smith. Part Two: Prognostic and Diagnostic Omens, Tablet I”, Revue d'Assyriologie, vol. 85, pp. 137-167, 1991.: 139-140 and Gabbay, 2012, “Akkadian Commentaries from Ancient Mesopotamia and Their Relation to Early Hebrew Exegesis”, Dead Sea Discoveries, vol. 19, pp. 267-312, 2012.: 282-287 contain some discussion on the education aspects of Mesopotamian commentary writing.

- 1. This page follows closely the detailed description of the socio-cultural mileu of the commentaries in , Babylonian and Assyrian Text Commentaries. Origins of Interpretation. Ugarit-Verlag, 2011. PP. 262-316. The distinction made there between “libraries” (used for groups of tablets excavated in a single spot) and “tablet collections” (tablets that can be grouped together because of their colophons) is also adopted here.

- 2. Not including the extispicy subseries Multābiltu or the lexical commentary Ḫargud, which are mostly represented by Nineveh tablets.

- 3. Note that it cannot be excluded that some of these commentaries come from Babylon, since not all tablets from the British Museum’s “Sippar Collection” were actually found at Sippar.

- 4. See , Babylonian and Assyrian Text Commentaries. Origins of Interpretation. Ugarit-Verlag, 2011. Pp. 335-336.